In 1967, Boston was not a baseball town and who could blame them? The Red Sox hadn’t contended for a pennant since 1950, and hadn’t even had a winning season since 1958.

In 1967, Boston was not a baseball town and who could blame them? The Red Sox hadn’t contended for a pennant since 1950, and hadn’t even had a winning season since 1958.

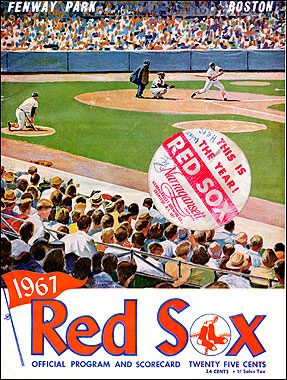

Just over ten thousand a game had come in 1966 to see the Red Sox lose 90 games. But in 1967 it all changed, with an Impossible Dream reinvigorating the Red Sox, interest in baseball in New England, and Fenway Park.

The Red Sox had been run like a country club for years. The rules of the time allowed owners to cut salaries after a bad season, but owner Tom Yawkey never cut anybody’s (Ted Williams had to beg Yawkey to cut his after a poor 1959). “They say there’s no sentiment in baseball, but I guess I have more than most,†Yawkey sheepishly said in a Sports Illustrated article. In many other ways, Yawkey had checked out, spending more time on his South Carolina estate at Fenway Park. Manager Billy Herman proclaimed to be a disciplinarian, but the Red Sox, to most people’s appearances (including the players), still seemed like the same old club. As second baseman Chuck Schilling said to Sports Illustrated, “They told me when I came here, that there were a lot of guys who didn’t care much whether they won or lost as long as they had fun.†Dick Stuart, whose predilection for errors and strikeouts was only matched by his home runs and his own television show in Boston, seemed the archetype. Stuart was handsome, funny, and talented. Nicknamed Dr. Strangeglove for his awful first basemanship, he once had a license plate that read “E3â€.  His mantra was “I’m not paid to field, I’m paid to hit!†But Stuart wasn’t as good a hitter as he thought – he didn’t hit for a high average and he didn’t walk, plus he also grounded into a ton of double plays – and he didn’t give a shit. “He was the poorest excuse for a caring ballplayer I ever saw,†said Dick Williams. Stuart even once successfully argued to an umpire that he wasn’t hit by a pitch with the bases loaded so he could stay at the plate. He struck out.Â

Just to top off the rot, Fenway Park, perceived as aging and antiquated in an era when perfection was the Astrodome, was widely considered to hurt the Red Sox. Its cozy dimensions and the presence of the Wall in left field was believed to lead to sore-armed pitchers and pull-happy hitters, too eager to take advantage of the possibility of lifting a ball over the fence for a home run and striking out instead. A new domed stadium in Boston was on its way and the Red Sox were going to be its centrepiece.

How, therefore, in this situation could winning happen? The first piece of the puzzle was a quiet overhaul of the farm system in the early 1960s. New leadership saw the farm system begin to feed significant amounts of young players to the Red Sox – the Red Sox lost 100 games in 1965, but they lost with kids. Carl Yastrzemski, Jim Lonborg, Rico Petrocelli, local hero Tony Conigliaro plus supersub Dalton Jones were 25 and younger. George Scott, Joe Foy, Mike Andrews and Reggie Smith came up in 1966 and Jose Santiago was bought from the Kansas City Athletics. Santiago was a savvy piece of business from new general manager Dick O’Connell, promoted when Mike Higgins was fired in 1965. O’Connell, a former business manager for the Sox, was inexperienced in baseball matters and was assisted by vice president Haywood Sullivan. But the Boston native and lifelong Sox fan demanded competence and he fired manager Billy Herman, replacing him with Dick Williams, who managed many young Sox at their Triple-A farm team in Toronto.

Williams represented a change in direction from previous Sox managers. He was just 37 when he took over the team and he’d even played with several members of the 1967 Red Sox, having only concluded his playing career in 1964. Williams had seen country club baseball upfront. “I was around here when all anyone thought about was himself. We’ll have no more of that. Anybody who plays for me will put the ballclub first and himself second,†and he meant it. In spring training, he drilled them in fundamentals for hours, teaching them the basics previous managers didn’t. His pitchers played volleyball, a surreal development that attracted press criticism until Williams explained that not only did it encourage fun and camaraderie, but also took up dead time and helped get his pitchers in shape for the season.

The final piece of the puzzle was Carl Yastrzemski. Yastrzemski had been hyped as the next Ted Williams since the Red Sox signed him away from Notre Dame in 1959. He’d won a batting title in 1963 and in 1965 he led the American League in on-base plus slugging, but had not risen above the level of being a good player on a bad team. Yastrzemski was entering his eighth major league season and decided to shape up. Having graduated from college the year before, Yastrzemski no longer had winter classes to take up his time and a local fitness trainer, Gene Berde, whipped Yastrzemski into the best shape of his career.

Still, even with the young talent, new management on and off the field, and a new, bigger Yaz, nobody took the Red Sox too seriously. The Red Sox had finished 1966 well – they’d gone 45-43 over the last three months of the season – but they were still picked to finish in the bottom half of the American League. When Williams proclaimed before the season that he thought the Red Sox would win more than they lost, people nodded, smiled, and wrote the Red Sox off anyway.

The first sign something might be different came in the third game of the season. Billy Rohr, a pitcher on his major league debut, took a no hitter into the 9th inning. Tom Tresh hit a long flyball to left that Carl Yastrzemski made a tremendous diving catch on, leaping with his back to the infield before making a barrel roll, holding the ball up as a trophy. Rohr lost the no hitter on a single by Elston Howard with two in the ninth (throwing a two-strike curve that the umpire missed), but the tone for the season was set.

The Red Sox kept their heads above water until the All-Star break, going into baseball’s mid-season siesta 41-39, six games out of first. They’d won with dramatics – Jose Tartabull hit a single to win a 15 inning thriller over the Athletics, 11-10 – and they’d won with feistiness, beating the Yankees on a Wednesday night in the Bronx that saw a brawl after Yankee pitcher Thad Tillotson beaned Joe Foy.

But the fun really started after the All-Star break. The Red Sox won ten straight games, their longest winning streak since 1950, and 15,000 fans came to greet the team at Boston’s Logan Airport when they arrived home from a six game road trip versus the defending champion Baltimore Orioles and Cleveland. The Red Sox had gone from five games out to within a half game of first, and Red Sox mania was born. Weak-armed Jose Tartabull threw out Ken Berry to win a ballgame versus fellow pennant contenders the White Sox, Jim Lonborg (deciding to throw inside for the first time in his career) kept winning and fans kept coming to Fenway Park. The Red Sox had become a sensation; they had drawn just over eight thousand for Opening Day, but were now playing in front of full houses at Fenway Park. You could walk out on a hot summer night in Boston and follow the game through radios and televisions blasting through open windows.

Carl Yastrzemski, meanwhile, was having an exceptional season. The new Yaz was hitting .308 with 35 home runs, a .401 on base percentage and 95 runs batted in. He had never hit more than 20 home runs in a season, but had accrued nearly twice as many with one month left. He appeared on the cover of Life magazine and was increasingly being acknowledged as the certain choice for Most Valuable Player. George Scott hit .303 and Rico Petrocelli was one of the best offensive shortstops in baseball. Lee Stange and Gary Bell were pitching well behind ace Lonborg and John Wyatt was one of the league’s better relievers. This combined to put the Red Sox into the thick of a four team pennant race, with the Chicago White Sox, Detroit Tigers and Minnesota Twins all neck and neck coming into the final weeks of the season.

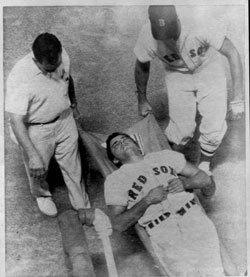

Unfortunately, Tony Conigliaro wasn’t to be a part of it. The East Boston native, who had hit a home run in his first game at Fenway Park as a 19 year old, who had won an American League home run title at 20, and who crooned on TV in his spare time, was beaned by a Jack Hamilton fastball versus the Angels. The pitch crushed his cheekbone and severely damaged his retina. The right fielder, in the midst of his best season, could no longer play in 1967. By a stroke of luck, the Red Sox signed outfielder Ken Harrelson, who had been given an unconditional release by the Athletics. Nonetheless, their offense was damaged.

Fortunately for them, September was the month of Yaz. Yastrzemski put on a show that few, if any, baseball players have ever put on before. Yaz hit .417 for the month of September with 9 home runs and 26 runs batted in. He got on base over half the time and slugged .704. In the last two weeks, he hit an astonishing .522, putting the Red Sox in a position to win virtually on  Chicago fell away and in the last weekend of the season, the Red Sox were to host the Minnesota Twins while Detroit was in California playing the Angels. A three team pennant tie was possible, and a split in Boston with three out of four from the Tigers would produce a three-way tie. The Red Sox won the first game on a home run and four runs batted in by – who else? – Carl Yastrzemski while the Tigers split their first doubleheader.

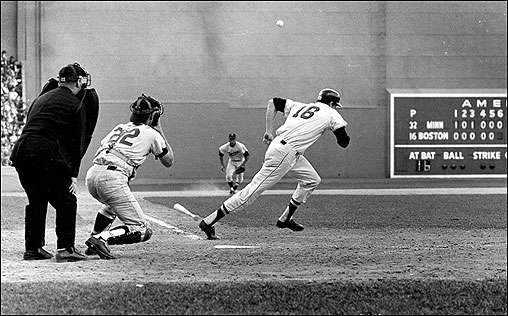

In the final game, the Twins raced out to a 2-0 lead against Jim Lonborg. Boston’s best was going for his 22nd win of the season and Dick Williams had confidence in Lonborg as he led off the 6th inning. Lonborg noted third baseman Cesar Tovar was playing deep, and to the surprise of all, deftly executed a bunt down the third baseline for a single. Jerry Adair and Dalton Jones singled, loading the bases for Carl Yastrzemski. His seventh hit in eight trips to the plate in the series tied the game at two. Ken Harrelson hit into a fielder’s choice which scored Jones, then two wild pitches scored Yastrzemski, before a Harmon Killebrew error made it 5-2 Red Sox. Lonborg shut them down the rest of the way, the denouement a soft pop up to Rico Petrocelli that set up pandemonium.

But there was still a game to be played: the Tigers had won the first game of their second doubleheader in two days, meaning if the Tigers won again, there would be a one game playoff at Fenway Park. But they lost, and the Red Sox had their first pennant in 21 years. Tom Yawkey said it was the happiest day of his life. Carl Yastrzemski, with his Saturday home run, tied Harmon Killebrew for the league lead in home runs, making him the first man since Mickey Mantle to win the Triple Crown for leading the league in average, home runs and runs batted in. He’s the last living man to do so. Unsurprisingly he won the MVP, while Jim Lonborg won the Cy Young Award for leading the league with 22 wins and Dick Williams won Manager of the Year. The Red Sox had had an extraordinary turnaround, going from one of baseball’s most stagnant franchises to pennant winners, breathing new life into themselves and New England.

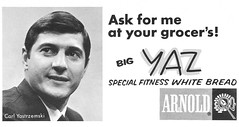

The legacy of the 1967 Red Sox is multi-faceted and rich, even if they didn’t win the World Series and the team never reached the same heights again (only Petrocelli and Yaz played for the 1975 American League champions). Carl Yastrzemski became a New England icon and freezers to this day still have 40 year old frozen loaves of Big Yaz Bread. The Red Sox led the American League in attendance in 1967, drawing over twice as many fans as 1966. They would lead the league in attendance six times in nine years, and not drop out of the top two for over a decade. The increase in interest remains to this day. Those fans coming to Fenway Park increased interest in the stadium itself; like the backlash to slum clearing and other old buildings being knocked down for shiny Modernist replacements, fans revolted against the new stadium as unnecessary and a waste of taxpayer money. Fenway’s lack of amenities and quirks were now part of its charm, not an embarrassment.

Has anyone read “The Little Red (Sox) Book” by Bill Lee? It’s a very cleverly written alternative history of the Red Sox, looking at how the team could have had so much more success in their early years had a couple of events panned out slightly differently.

Yeah, I have. It’s a fun little book. Bill Lee is definitely someone I would consider writing about in the future, though I’m going to try and mix it up. Otherwise every article would be about the Giants, New York baseball, or the Red Sox.

Maybe in a few months when I’m back in the States on holiday and I have my library at my disposal. There is a fantastic Peter Gammons book called Beyond The Sixth Game – one of the best books ever written on one team and one period of time – that has a laundry list of the best Bill Lee quotes.